In March, I had the privilege of staying for two weeks at the Sri Lankan Buddhist Vihara in Kambah, ACT.

I arrived after being quite sick from gastro during a heatwave in the middle of which there was a long power outage. I was feeling pretty rotten! But the monks at the Kambah temple were so friendly and helpful, giving me plenty of time to rest and recuperate. I was very moved by their kindness. Given the monks were so good-hearted it wasn’t a surprise to discover that the community of lay supporters were also very caring people, too. They really care about their monks and the temple, and look after their community very well. I felt as though I was in a beautiful bubble of kindness in Kambah!

Every morning and evening, lay people come to the temple to offer a Buddha Puja, chanting some verses of Dhamma and afterwards offering some refreshments for the monks or helping out around the temple. The monks also receive regular invitations from lay devotees to visit their home to offer a meal. This is a beautiful tradition that dates back to the time of the Buddha. Many of these invitations are memorial occasions where families remember their departed loved ones through the meritorious act of offering food to the Sangha and sharing the merits with their departed loved ones.

Traditionally such ceremonies are performed seven days after their loved one has left this world and then again after one month, three months, and one year, becoming an annual event after that. This practice of coming together with family and friends to do something positive to remember dear ones is one of the most beautiful aspects of Sri Lankan Buddhism and has taught me a lot about the different ways we can grieve. Whilst there may be lingering sadness about losing someone, this is somewhat assuaged through the positive force of doing something kind and generous in their memory, and especially by joining with friends and family for support through these stages of grief and loss.

These ceremonies also give the living an opportunity to connect with their spiritual practice and to hear the Dhamma from the Sangha. During my stay in Kambah, I attended many such events and was asked to give short Dhamma talks for the devotees related to the occasion (death is one of my favourite themes!). The frequency of these memorial danas was a powerful reminder of the Buddha’s teaching on impermanence; every being that is born must die, this is an inescapable and universal truth.

As a monk, I feel very fortunate to be invited regularly to attend these commemorative events because they keep me connected with the profound truth of impermanence and help me understand the precarious nature of our existence. The Buddha recommended frequently reflecting on death to develop a sense of urgency in our spiritual practice and to help shift our focus towards living a good and meaningful life. When I meet with families and friends remembering their departed loved ones, I’ll often share the Buddha’s teachings on the brevity of life and point towards the bigger picture perspective of our suffering in the cycle of samsara, so that hopefully listeners can leverage their experience of personal loss to see the benefit of leading a good life and make the most of our time on Earth to develop wisdom. Afterall, death is our constant companion, so best to make a friend of death!

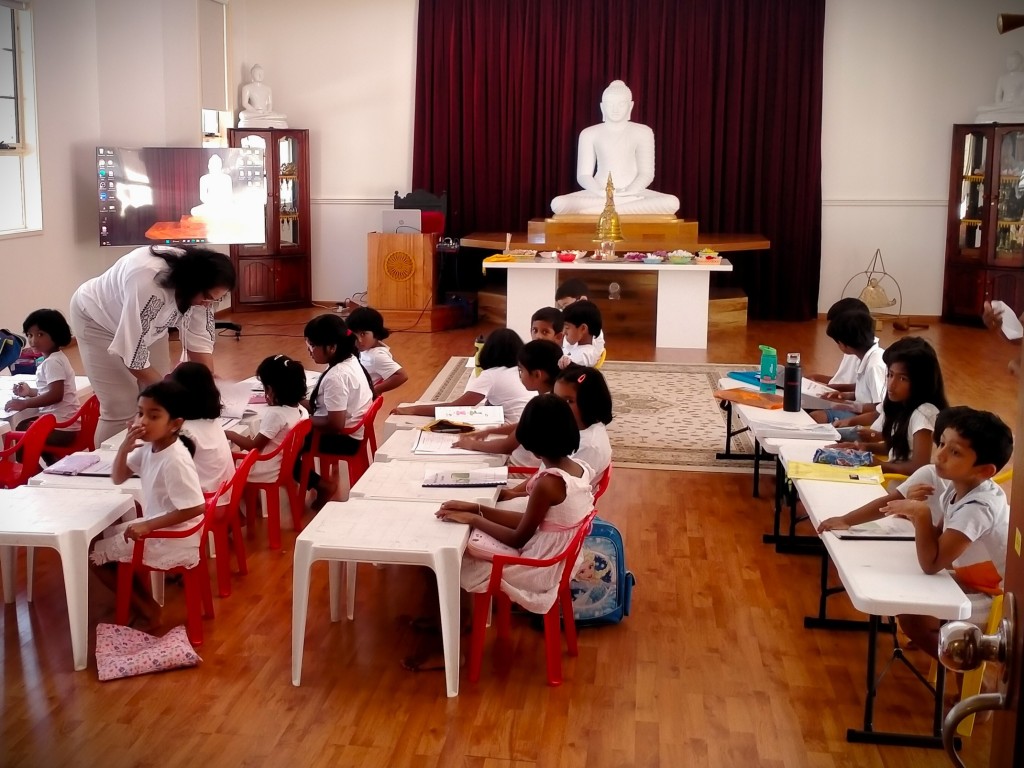

Children EVERYWHERE!!!

Whilst many of the events I attended with the Kambah temple community were focussed on death, the weekends were the complete opposite; a real celebration of life and vitality! Every Saturday, children of all ages take over the temple, attending Dhamma school followed by Sinhala language class. There’s a wonderful energy that children bring into any space; they come with their smiles and laughter, infectious enthusiasm and a fair amount of chaos.

It’s great that these young people have an opportunity to come together with their diasporic community to learn a language and get to know about Sri Lankan culture. The migrant experience is often characterised in terms of being estranged from the rich fabric of food, language and culture of the country of birth, being in a new land where these familiar things are largely absent.

For the children of migrants, this experience of alienation is even more acute; they may not have ever visited the country of their forebears, perhaps they don’t speak the language, or understand the significance of many of the cultural activities their parents and grandparents engage in. This can be particularly true when it comes to religion. For many migrants, Buddhism is intimately wrapped up in the culture and language of their home country. This is completely understandable and natural. These things provide a sense of connection and continuity of traditions and practices for migrant communities, which is very important.

However, for the younger generations of diaspora communities here in Australia, the intermingling of culture and language in community religious activities can have an opposite effect from the sense of deep connection that their parents feel, and instead, can end up alienating young people from religious places and spiritual practice. This is because often, the children of migrants lack the culturally contextualised understanding of even basic things their parents took for granted in their home country and find it difficult to relate to religious ceremonies and activities. Australian Sri Lankan young people often talk to me about sitting through long cultural events and ceremonies without really knowing what’s going on, or listening to Dhamma talks that they can’t understand because it is spoken in Sinhala. For these young Buddhists, there is a danger that they will only associate their spiritual practice as something that their parents and ethnic community do. Or that their religion is more about language or culture, or that their spirituality is merely a ceremonial practice, something done on holidays or special occasions only. This is sad because they may never see Buddhism as something that has the enormous potential to benefit them on a personal or existential level.

For these reasons, the Kambah community were really keen to have an Australian monk and a native English speaker talk with the young people for the Saturday afternoon programs whilst I was in residence. I spoke to the students about the diversity of Buddhist experience, reminding them that they were part of a long and rich history that transcended culture and place, and which goes beyond things like skin colour, nationality, language and other cultural attributes.

The parents of these children value the Dhamma because they see so many benefits that can come from understanding the Buddha’s wisdom. Out of compassion for their kids, their sincerest wish is to establish their children in the Dhamma, so that it can be a support for them now and in the future. Children—being children—tend to ignore their parent’s advice out of youthful contrariness and because they need to learn their own life lessons whilst following their own path. However, in these fun-filled afternoons of friendship, culture and community at the Kambah temple, a valuable seed of dhamma has been planted and will hopefully ripen in the future.